Artist and animator Edwin Rostron discusses automatic animation, exploring the process of painting, finding abstraction from template forms.

by Ben Nicholson

Image courtesy of the artist.

Edwin Rostron has been creating and sharing striking experimental animations for well over two decades now. Not only has he brought exceptional animated moving image work to screens as the mind behind Edge of Frame, but his own treasure trove of films is filled with mesmeric formulations and unforgettable imagery. Films like Visions of the Invertebrate (2011), Our Selves Unknown (2014), and The Asphodel Phases (2013-19) have screened internationally from Ann Arbor to Helsinki, from Barcelona to Montreal.

On the occasion of a joint exhibition called I’m Here But I’m Not a Cat, organised in collaboration with Daniel & Clara, Adonia Bouchehri, and Duncan Poulton, ALT/KINO sat down with Edwin to discuss his work.

ALT/KINO: I'm keen to hear from each of you about the concept for this exhibition. Perhaps, folding in a bit of background about your own practice, could you speak about why this idea was interesting to you, and how the notion of going beyond on-screen work is giving you something different?

Edwin Rostron: I think the idea for the exhibition came out of realising, as a group, that although our practices are quite different in many ways, there are also significant things that connect us - particularly at this time. This seems to centre on expanding our moving image practices into more physical works. I've directed my work towards animation for quite a long time. Since I started making animations, which was over 25 years ago, it's been like a place for me to put all my work in drawing, collage, or other media. Partly of course because I was excited by the form and partly, I guess, because screening films is more straightforward than showing work in exhibitions, and I was really mainly concerned with making rather than showing. Then around 2017-18 it started to feel increasingly arbitrary to just do that - to have everything end up only as a short film. I started to think about showing my animation alongside my drawings and paintings to reframe the context for my animation work. And around the same time we started the discussions which ultimately led to this exhibition. I have shown work in a few exhibitions over the years but I had my first solo exhibition last year [at Deptford Contemporary], where I showed a lot of drawings and paintings alongside some animation, and which I approached with a lot more focus. The experience of putting it all together and conversations around it all really clarified that, for me, the way I exhibit my work is really another stage of making it.

A/K: Has this different way you're now thinking about the endpoint of your work had a noticeable impact on your practice. Do you think it's changed your process?

ER: Even before the pandemic I remember thinking that it felt increasingly futile to only send stuff to festivals, that I was never going to find that completely satisfying. I think that connects to starting to make more paintings and drawings, but I also just really wanted to develop my painting more anyway. To me animation feels like a space where there is still lots of new and interesting stuff you could do - not that I’m necessarily doing it! - but for a long time painting seemed overwhelming, maybe too difficult to even broach, because of the whole history of painting, and my lack of knowledge and ability just seemed abundantly obvious. With animation, I was like: "It's worth a try... I can have a go.” I felt less like that with painting, more inhibited. And it's not like that's really changed completely now, but it's more like I feel like I can try and find my own way with it, which maybe I didn’t before. Maybe I can embrace the failure more easily too! And after making animations for 25 years, it was also just really appealing for me to try and do something new. I had ‘used paint’ in several films and painted into my drawings on paper quite a bit too, but the big thing for me was moving to painting on board - and making a painting that is primarily ‘a painting’, not something that might always be an ingredient in a film. It seems like quite a simple shift, but for me it's quite a different mindset. Maybe when you paint for an animation you are really actually animating - or filmmaking - rather than ‘painting’? I guess there aren’t such clear boundaries between these things. But as soon as I started painting for no other reason than to make a painting, I realised what a totally different process it is to animation, but also even to drawing. It's just very compelling as a process too, and with a new medium you make quite dramatic leaps or shifts quite frequently, and you progress in a very different way to when you've been doing something for 20-odd years. More fraught but more exciting maybe!

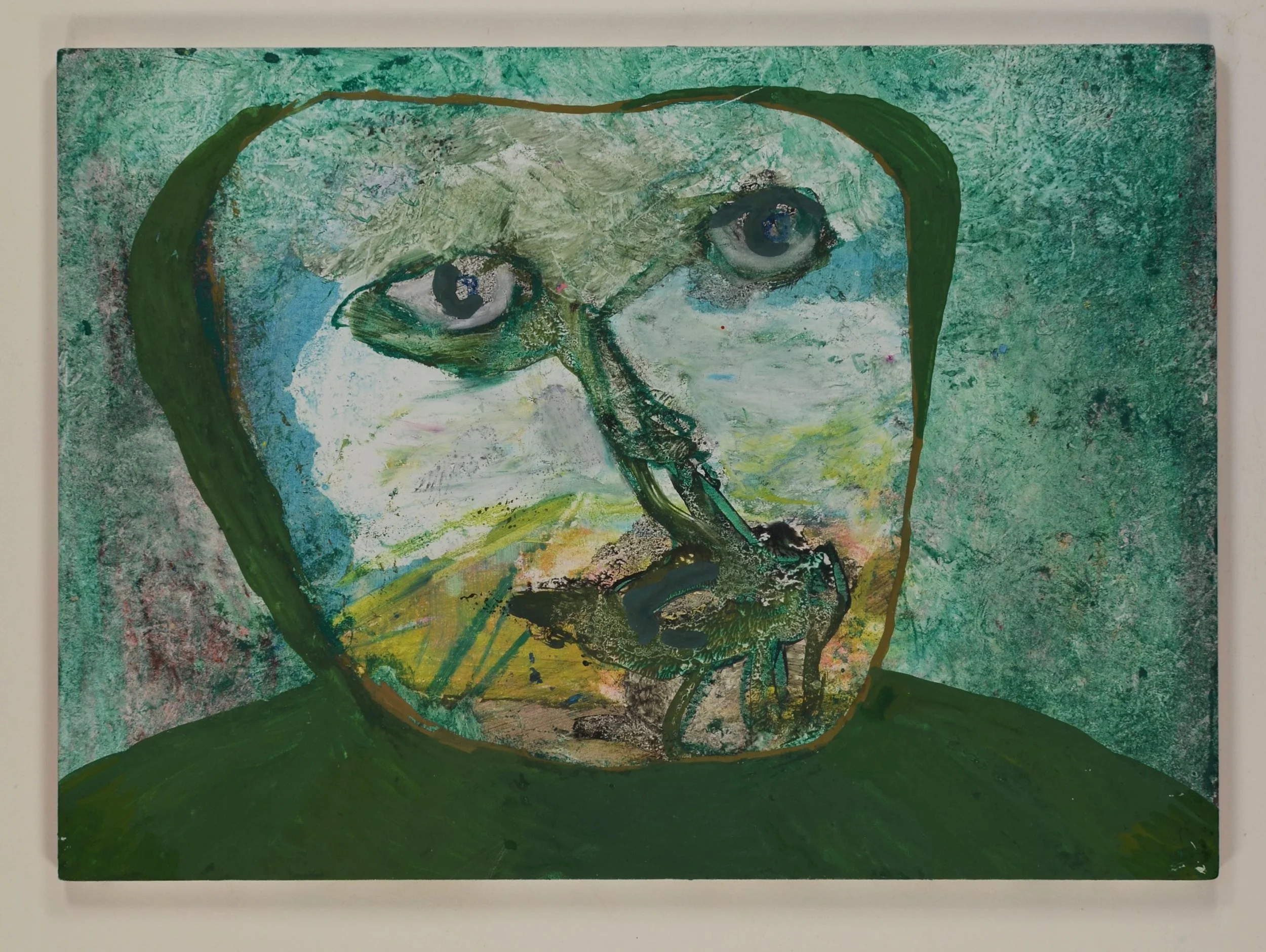

A/K: Coming on to the exhibition, then, I wanted to ask you about some of the work that you're showing. One of the things that really struck me upon seeing your paintings was the figures and faces. They're motifs that are hugely prevalent across your work - your short films often feature faces. I wondered if you could just speak a little bit about what you find interesting in doing them and also, maybe, whether you've approached them differently in the context of these paintings as opposed to your line drawn compositions for animation.

ER: I always drew a lot as a child - drawing was always a big part of my life and I have just tried to carry on doing it as much as I can. I suppose I've always drawn in a more automatic, playful, doodley kind of way than ‘proper’ observational drawing, and instinctively and somewhat predictably I have always drawn faces and figures as a starting point, moving to abstract or deface or embellish them as I go on. I guess faces are an obvious thing that just come out for many people when they draw. It's a kind of compulsive thing for me, and I have tried to stop myself from doing it, because I’m aware it can seem a bit obvious and limited. But that doesn’t usually work so on the whole I try to embrace it, or at least accept it. I guess when I started painting, I primarily wanted to develop and progress my painting first and foremost, so I just went with the subject that came out most naturally - heads and faces - as a basic structure that I didn’t have to think about. I thought maybe let's just really overdo it and try to get it out my system - but I’m still working on that.

I would say, they're not based on anybody else. I don't think they're to do with other people. I can call them portraits, but they're not really portraits of any real people. I think they are much more to do with me and the moment that I do them in. An expression of something, some energy or whatever unconscious things are going on in and around me. For me, the face is just a kind of template form, something to start from, but the thing that I always find really bizarre and interesting is that the difference between a line of one angle or another, or a colour in a certain place, when you're doing a face, is the difference between one complete identity and another. They do seem to have specific identities, to me. I guess I want them to have presence. So, that weird jump between it being abstract and something that you can connect with in the most direct way - there's nothing that you connect with more than a face, really - is endlessly interesting to me.

Image courtesy of the artist.

A/K: But there are also these other tree forms in the exhibition’s paintings, right?

ER: Yes, after having continued with these faces - which I think I may be doomed to always do - I was looking for other forms that felt as instinctive and engaging as a face. For quite a while I did paintings of grids, which worked well, because it was like nothing and everything - as with a face - completely meaningless and yet there’s the potential to have all the meaning you could possibly want within it. Then I struck upon this other form, which was like a tree, but also an explosion. I went to the recent Cezanne exhibition at the Tate, and I think I engaged with his work in a completely different way than I may have once done because I had started painting quite a lot myself. I saw this particular painting of a bouquet of flowers [Grand Bouquet of Flowers, c.1892–5], and it had quite a big effect on me. It did hit me like an explosion and it kind of looked like one too. Later I was messing about in the studio and had got a postcard of the painting. I just sort of took the line structure from within the painting and started to use that as a basic form. Then I just got really into it; the initial excitement of seeing the painting was still in me, and the actual shape just started to work - to get me into some new interesting places.

A/K: You mentioned automatic drawing a moment ago and that is what your animations often feel like. Do you think that fundamental desire to, as it were, let the drawing reveal itself is the reason that you are attracted to geometric patterns and these visual templates?

ER: Exactly, yes. Like painting a grid, my drawn geometric animations are kind of meaningless and yet you find all sorts of connections or ways of thinking about them that come and go as you work - but it's completely fluid - like the animations end up being themselves. I guess it's important to me that they stay open - for me as I’m working and then in the end for the viewer. Making them, you have to be engaged and so you may temporarily assign lots of meaning to certain things, but it never really holds. It's just this thing that ultimately resists being about anything fixed. Within the animations it becomes about the movement or the animation itself, some aspect of the process in motion. In the painting, it becomes about something other than just the subject. I suppose it's about having a kind of living feeling about it, some kind of autonomous life of its own. I think there's a connection between reducing my materials - to just a pencil, or just markers, or whatever - and reducing my subject to just a face or just a grid. It stops you making decisions, or choices, in a way that totally allows you to let go and get to something else. You're not thinking about the thing as a thing. You're able to let whatever energy is inside you at that moment, and wants to come out through your work, happen. It's sort of a convenient structure, really; the more you've got to, like, decide things consciously, the harder it is to let that happen.

A/K: I've heard you mention before how you use the thinness of the cheap paper, and the resulting seeping through of marker ink, as part of your method. Obviously, we think of automatic drawing as producing a still image - we think of letting your hand do its own thing. Can you speak a little bit about the process of automatic animating?

ER: Yeah, sure. Normally, if I’m working with hand-drawn animation, I’m re-tracing the previous drawing, but bit by bit changing it into another position or shape. My work is fundamentally improvisational so I am usually not entirely sure where it's going more than a few seconds ahead but usually I do have a small step ahead in mind. At some point I wondered what would happen if I were to let the drawing find its own direction and shape over time, by just re-tracing with no conscious intention, no end shape or position at all. I wondered if an overall direction would emerge, and what new shapes would form? This resulted in a different kind of end result, and some of my recent work oscillates between this aimless, hovering metamorphosis, and the more guided changes from one form into another distinct form. A lot of my creative practice is to do with levels of control, and losing control. With automatic drawing it's the same thing; you're drawing a line but then you might let it go somewhere else, then you might do something wild, you don't know what's going to happen next and you must deal with that and make sense of it. The same with painting to an extent. It's like a game where you're just constantly setting up problems for yourself to deal with and create the next problem. And then in an animation the film itself can show this actually happening.

With most of my drawn animations I’ve used a light box, tracing from one piece of paper to another over the top. During the pandemic, I was making many tiny micro animations, which became my film Fragments. One of those longer fragments is where I started this ink-bleeding thing. I'd been drawing and painting on these cheap A6 pads with really thin, smooth plain paper. There's something about this paper that just works really, really well for me - whatever pens or paint I'm using. I think it's partly because - psychologically - they're the same pads that I have things like shopping lists and random notes on, so the stakes are very low. The pads seem just like part of my everyday life rather than existing in some separate ‘art’ zone. Anyway, I noticed that when I used certain marker pens on them, it would bleed through to the next sheet, so on the next page you get this kind of reference mark of the previous thing, cutting out the need for a light box. It was just a way of animating that I'd not come across before. You can just animate with the notebook and pen - a limitation of means which inherently attracts me. Also, the ink creates this kind of smudging effect because each drawing has the ink bleed from the previous drawing on it which I like as well.

Image courtesy of artist.

A/K: The last thing I want to ask you about - which comes to mind because I love the way you use it to upset the linear temporality of Jam Sandwich, which is part of the exhibition - are loops and repetitions, which are forms that recur across your animation work.

ER: I think there's a few things on that topic. For a while I have been exploring quicker ways of making animation. For a long time I was only making drawn animations, usually with 12 separate drawings for each second of the entire film. Obviously, that just takes a very, very long time to do. If that's the way you want to work - and sometimes it is the way I want to work, it can be extremely rewarding in many ways - that's great. But I wanted to make more work, I wanted to make quicker more spontaneous work, and partly as a result I got into this new way of working using my phone as a camera; and just using a few images - often one or two - and activating them in different ways through the camera and editing to create a sense of movement - animation - from the most minimal of ingredients. It was spontaneous, and physical, and raw and so quick that I could make them before I even knew I had made them - which is like the way I draw. To get it out before you can even think about it. I guess then the looping repetition comes from trying to just hold those tiny sequences on screen for a while. To me they seem to be somewhere in between a film and a still image - like movement and stasis at the same time. These works, which form most of my film Fragments, then started to affect the way I was thinking about the earlier more traditional kind of drawn animation I was doing, and so ideas of loops, shorter works and repetition started to feed into that way of working too, as in the three screen piece Jam Sandwich in this show.

This piece is an experiment in making drawn animation specifically for a gallery context, so it's meant to be part of an environment - on small screens on the wall with my paintings, and amongst other works by other people - not the only thing going on in the space. I also wanted them to have the feeling of being continuous and ongoing, and the looping is integral to that; always changing yet always the same somehow. The three animations are also based around recurring heads and faces, alternating with abstract compositions, which meander in and out of each other. They are completely improvised and utilise the ‘automatic’ animation approach we discussed earlier a bit too, but in order to make them continuously loop I did then have to ‘consciously’ bring the final drawings back to match the original one. I haven’t done the best job of making them loop, and perhaps that’s partly because of my instinctive feelings about a lot of animation being quite slick these days. But also I think that animating for a long time has also made me particularly interested in the idea of discontinuity too. I do feel like the flaws in my work are central somehow - the way the animations speed up, slow down, jar slightly - gives them their own particular life and personality that is completely specific to themselves.

I’m Here But I’m Not a Cat runs from 22 Sep - 1 Oct at SET Kensington.

Screenings of moving image work by the artists take place at Close-Up Film Centre on 23 September.

We have also conducted interviews with Adonia Bouchehri, Daniel & Clara, and Duncan Poulton.