Jodie Mack, maker of cine-panegyrics and joyful dissections of pop and folk culture’s lost and found, was recently featured in a free streaming programme curated by Ecstatic Static.

Blanket Statement #1: Home is Where the Heart is (Jodie Mack, 2012)

Ecstatic Static recently presented five of Jodie Mack’s short animations from 2012-2017, to provide a brief but filling introduction to her work. It also saw a major artist flitting from discovery to discovery, testing out how she perceives, and so how we could experience, the make-up of the world.

Mack arrived at cinema, and specifically experimental animation, in 2003 and quite early on became conscious that she wanted to make work that bucked rather than beat the dead horse of realist representation. This led her down the abstract route, including the use of camera-less film, and the figurative through unconventional means.

However, at the turn of the next decade, she began to gravitate away from direct film, paper and plastics towards the increasing use of fabrics and other textiles. She also switched from a mix of digital and film to almost exclusively using 16mm, a form more adept than most in calibrating one’s focus to the nitty-gritty of texture and therefore thinking about its implications. This forged a new path for her work, beginning with films like Harlequin (2009) and Posthaste Perennial Pattern (2010) and furthered with showcased films like Blanket Statement #1: Home is Where the Heart is (2012), Undertone Overture (2013) and Razzle Dazzle (2014).

Plaid, quilts, lace, and silk, with their rich patterns and designs, and later precious stones and technological objects, allowed her to continue to work in a non-realist way but with subjects whose mix of interchangeable, set properties and patterns with unique yet pliable details, allowed her to work abstractly and summon from a well of near-universal and particular associations, emotions and even personalities. Mack has professed, and shown very clearly in her work, an affinity for the inanimate and ephemeral. This inclination and the new palette and tools have allowed her to explore a hinterland between narrative and experimental cinemas, that she couldn’t have necessarily found using more blank-canvas-like materials or modes already heavily mined.

Undertone Overture (Jodie Mack, 2013)

Blanket Statement #1 and Undertone Overture, two peas in a pod, as they are both top-down shot, flicker films, consisting of rapidly intercut objects and images, are brief but outstanding ventures into this new approach.

The former is a short and simple but rich kaleidoscope, featuring a cycling view of different quilt patterns, shown varyingly in close up detail and arranged together in spinning geometric patterns. The soft and springy-seeming textures and the dynamic, warm colours embossed, exude a cosiness and comfort. This sensation co-exists with a distancing effect, located in the very strict shape of the film and its disillusioning soundtrack. The elemental, throbbing rhythm of the celluloid’s sound strip running through the gate, alongside treated, electronic syncopations.

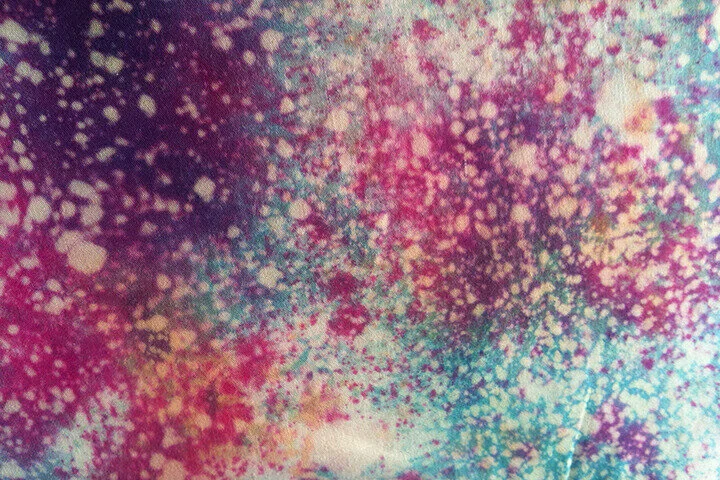

Undertone Overture is a more ambitious work, with a longer runtime and more dynamic soundscape. Ten minutes long and starting with a steady editing rhythm until it builds to a breakneck zenith before winding down again, it consists of successive, hyper-speed, shots of different tie-dye patterns on grey cotton. On the soundtrack, instead of the medium ticking away, there is the sound of waves crashing. The combination of these sounds and swirling coloured fabrics conjures in the mind’s eye notions of summer, the beach, holidaying, and all-around fun, but then the film ramps up, and these corporeal, emotional associations collapse into a heady transcendence. What were recognisably tie-dye shirts because swirling, gesturing entities of colour, pulling the film away from the shore and closer to the dyeing process’s otherworldly-minded roots. Since ancient times, in many cultures across Asia and Africa, as well as in modern hippiedom, tie-dye has been a means of departing this existence and stable form for another, more spiritual, zone.

These two works were made and released in 2012 and 2013, in what was the most productive period of Mack’s practice thus far. Within the span of these two years, she produced eight short works, her first longer work, Dusty Stacks of Mom (2013) and the inaugural bout of filming for her second, The Grand Bizarre (2018). One of the marked qualities shared by these features is their live-action aspect, though it is no capitulation to realism. Instead, she has expanded her purview, beyond the top-down look at dancing and spinning materials, to take in and animate the world that contextualizes and produces them.

Something Between Us (Jodie Mack, 2015)

Something Between Us (2015) fits this development into the shape of a sweet serenade. A ‘musical documentary’, that casts costume jewellery as its performers, recalling Busby Berkeley, with his mechanized humans, or Fantasia (1941), with its magically limber animals and inanimate objects. We see the jewellery being manipulated by human hands, draped over, or shrouded in verdant greenery and swaying against the backdrop of a void. It’s the natural, the abstract and man-made words intermingling, becoming indivisible, as these rainbow-reflecting gemstones are echoed by the equally prismatic play of light on water, and both unmanipulated and heavily ordered birdsong mesh with an imitative, glockenspiel soundtrack.

Despite its joie de vivre, through its joie de objet, death hangs over this film. Mack has stated that she conceived it as an illustration of the undying connection between two then recently departed friends and life partners, historian of avant-garde animation Cecile Starr and filmmaker Aram Boyajian. Grief and reflection motivate the currently 2-film Wasteland series as well, which constitutes some of her most recent works as well as the future, with a third entry in ferment.

Wasteland #1: Ardent, Verdant (2017) was infused with her most synthetic materials yet; close-up shots of circuit boards and printed out images of red poppies in a field, symbolizing both succour and the grave. They rapidly alternate, fusing together by montage or pasted together in perverse exquisite corpses. The circuit boards, with their predetermined, designed shapes and intricacies, recall the Thomas Pynchon metaphor of the city from above looking like an enormous computer chip. Concoctions of civilization then, and yet coated often in dust, therefore subject to weathering and decay just like any living thing, and more tangible than the ostensibly natural poppies, which are presented not as images of objects but images of images and thus more abstract. They are the most, literally, two-dimensional subjects in Mack’s engrossing vocation as a charmer of objects and surfaces.

The programme Five Films by Jodie Mack ran on Ecstatic Static from 11 May - 2 June 2021. You can find more information on Jodie Mack’s work, and a number of her films can also be viewed, on her website: jodiemack.com.

Ruairí McCann is a Belfast born and based writer, raised in Sligo. He sits on the board of the Spilt Milk Music & Arts Festival, has written and edited for Ultra Dogme, photogénie and Electric Ghost, and is a contributor for MUBI Notebook, Screen Slate and Sight & Sound.