A collage film that is both a memorial to those that have been lost and designed to one day be lost itself, Theo Rollason explores the nature of Charlie Shackleton’s feature film The Afterlight, which exists as a single 35mm print.

by Theo Rollason

The Afterlight (Charlie Shackleton, 2021)

“Cinema is,” Jacques Derrida memorably insists in Ken McMullen’s Ghost Dance, “an art of ghosts. It’s the art of letting ghosts come back.” Charlie Shackleton’s The Afterlight is a film composed of fragments, whose cast are the souls of film history — stars of days gone by, all of whom are dead. Omar Sharif might appear next to Ruan Lingyu, Conrad Veidt alongside Barbara Windsor. It extracts from hundreds of existing works, mostly shot pre-1960, all in black and white, and of varying condition; pristinely preserved prints from 1950s Hollywood alongside scratchy, faded footage from the early decades of the century.

The narrative is loose. The film begins with characters walking alone at night through eerily empty, noirish streets, eventually converging on a bar illuminated by a neon sign: The Afterlight. Much of the film’s editing is suggestive of narrative events — scenes set at the bar, during a rainstorm, in an apartment — but there is no attempt to suggest absolute spatial continuity to the viewer. One more crucial detail: the film exists as a single 35mm print, which will deteriorate over time; edited digitally, all traces of the process were erased once the film was complete.

The Afterlight, then, takes as its starting point two conceits, the latter of which provocatively cancels out the former. First, with its cast of long-dead actors, it raises the idea of film as a haunted medium that promises its subjects immortality on the screen. Simultaneously, however, it forces us to confront the medium in its materiality — as something organic, corporeal, living — in order to remind us that cinema’s ghosts die too. Celluloid is a delicate material, subject to wear at the moment of projection, and to chemical deterioration even when stored in ideal conditions. Like a body, a film print is subject to injury, ageing, and eventually death.

***

The Afterlight belongs to an expansive genealogy of moving image works that foreground the materiality of celluloid by making the effects of time — especially decay — aesthetic experiences. Among the most well-known of such works are Nam June Paik’s Zen for Film (1962-64), a projection of a loop of transparent film leader on which the accumulated dust, dirt and damage becomes an integral part of the work itself; Peggy Ahwesh’s The Color of Love (1994), a slowed optical reprint of a kaleidoscopically degraded 8mm porn movie; and the found footage films of Bill Morrison, most notably his cine-apocalyptic feature Decasia (2002), consisting of optically reshot nitrate film in various states of chemical decomposition.

Andre Habib, writing on another found footage film composed of fragments of early cinema, Peter Delpeut’s Lyrical Nitrate (1990), suggests an “imaginary of the ruin” emerging from the context of the preservationist fervour of late twentieth century film culture, coinciding with the medium’s centenary. “The film archive is a strange tomb, characterized by what it lacks, and slowly decomposing,” Habib writes, noting that “the nature of the medium and what it records now command an immediately passionate, quasi-religious response, as if it were lives that were in peril” 1 . If we think of photochemical film as something living, the image of cinema’s history as a graveyard is an apt one: according to estimates from The Film Foundation, founded in 1990 by Martin Scorsese, “half of all American films made before 1950 and more than 90 percent of films made before 1929 are lost forever” 2 .

The Color of Love (Peggy Ahwesh, 1994)

Decasia (Bill Morrison, 2002)

In this context, it’s tempting to read The Afterlight — itself designed to disappear — as a rallying cry for film preservation. In an article written to coincide with The Afterlight’s premiere, however, Shackleton broadens the issue of “loss” beyond the traditional parameters. What’s really at risk of becoming lost isn’t just the individual films themselves, but the potential for a more expansive film culture — the promise dangled by the internet and streaming to “open up new audiences, and diversify cultural palates” that has proved so utterly false 3 . Shackleton’s article folds issues of decay and the “lost film” back onto issues of circulation. Physically lost films, of the kind shown being unearthed from the ground in Bill Morrison’s Dawson City: Frozen Time (2016), here also come to stand for films algorithmically “buried” on streaming services or platforms like YouTube.

Access to films that exist online is often determined by algorithms that tend to privilege the new and the already-popular, and may be withdrawn at the whim of the individuals and companies who contribute to or manage these platforms. Provocatively, Shackleton doesn’t limit this issue of viewership to digital. “Even film archives,” he writes, “are filled with prints that will never be screened, films that will never be seen. Jurij Meden, a curator at the Austrian Film Museum, calls such holdings ‘living-dead surplus’ and estimates that they account for 90% of archive collections” 4.

***

Archives, Derrida tells us, are structured according to the logics of power; such forces dictate which objects are cared for and venerated, and which are shut out, silenced. Looking to the history of film, commercial and geographical factors play an especially pronounced role in what gets lost and why. The Afterlight, in its very form, serves as a poignant testament to this reality. In an interview with Shackleton, he clarified that the film comprises of footage that has “been made available commercially in some form or other,” and therefore is already mediated by invisible layers of selection:

It can be tempting when you start cross-cutting between films from different places or different times, to see the medium as this great unifying force. But I was always reminded, because of the nature of the process, quite how much bias was built into what I had to work with. … Sometimes it’s hard to believe how differently two films can look even made in the same era, based on their perceived cultural or commercial value across the decades. Some of those Hitchcock films that are in there look like they were shot yesterday, whereas a lot of the films from outside of the United States and Western Europe have been much worse preserved just because much less has been invested in exploiting them over the years.

Unlike other works that appropriate their collaged footage from fiction films — Christian Marclay’s The Clock (2010) and Guy Maddin’s The Green Fog (2017), for example — Shackleton’s editing emphasises not just narrative content but the material surface of the appropriated works themselves: glossy high-definition images suddenly cut to dirty, jerky frames buried under blankets of scratches and grain. A stark contrast is revealed between the former, which exudes signs of care, and the latter, where even basic information is rendered almost illegible.

The Afterlight (Charlie Shackleton, 2021)

The Afterlight (Charlie Shackleton, 2021)

The effect is augmented by the film’s soundtrack: “silences” whose crackles and hums vary hugely from clip to clip, and the intermittent use of original music composed by Jeremy Warmsley, which is also subjected to varying levels of compression, distortion, and other sonic effects that imitate the levels of damage to the image being projected at a given moment, as if this soundtrack too has been subject to archival rot.

In my interview with Shackleton, he suggested that an early question that arose was negotiating whether to attempt to passively “reflect” what has been preserved and made available, or rather to push against an inequitable archive:

Ultimately, I settled for a compromise. I realised if I just reflected truly the state of affairs the film would’ve been 90% English-language, probably 80% American, and I think it would’ve been so overwhelming that it would have read like an intentional choice. … I ended up moderating that dominance in order to express it.

If The Afterlight is to be seen as a reflection on/of the archive — focusing less on what exists and more on how it exists in its commercially available forms — it also invites consideration of the absences that haunt it; “[e]very film archive,” writes Habib, “can be defined by its lacks, its losses” 5 .

***

In the close to his book The Death of Cinema, legendary archivist Paolo Cherchi Usai imagines the endless restoration and re-restoration of The Absolute Masterpiece® at the expense of those films that have been ignored by archives and financers: “while some festival advertises the premiere of a new version of The Absolute Masterpiece®, thousands of nitrate reels agonise on their shelves” 6 . The restoration of a few classics — or even the rediscovery of “lost masterpieces”— obscures the true scale of loss to the culture, as well as the problematic commercial agendas that motivate this work in the first place.

The Afterlight on tour.

Elsewhere, however, Cherchi Usai acknowledges that any attempt to bring the mass of genuinely lost films to light, in all their fragile materiality, is ultimately a doomed practice anyway. The promise of film preservation as a kind of immortality is as hopeless as the claim to fix still time itself; the inevitability of decay always prevails. The implication for the role of the film archivist — and, by extension, the media-archaeologically-minded filmmaker — amounts to

a radical change of perspective … Moving image preservation will be redefined as the science of its gradual loss and the art of coping with the consequences, very much like a physician who has accepted the inevitability of death even while he continues to fight for the patient’s life. 7

The Afterlight embodies Cherchi Usai’s ambivalent view, fighting the case for the film archive — as well as inviting us to consider its biases — and at the same time suggesting an alternative ethical approach to the moving image: letting die, learning to cope with loss. For many cinema enthusiasts, the latter might seem like a fairly repugnant proposition. Screened alongside The Afterlight at its London Film Festival premiere was a restoration of the anti-fascist short Europa (1931), a film long thought to have been destroyed by the Nazis. To apply the concept of “letting die” is especially hard to stomach when issues of historical marginalisation and censorship are taken into account. But Cherchi Usai’s work — and Shackleton’s film — need not be approached so nihilistically. Rather, both merely emphasise the necessity of a dialectical approach, wherein advocacy and acceptance exist side by side.

***

For all the talk of death and decay, the film I saw at its fifth public screening in 2021 was in remarkably good shape; any damage to the print was minimal, sporadic and hardly noticeable. Since then, The Afterlight’s sole print has made its way around the world, touring film festivals and local cinemas. Ahead of the film’s next screening — its fiftieth, at the BFI Southbank for its inaugural Film On Film Festival — I spoke with Shackleton again to find out how the film had changed. Not all that much, as it turns out; the strange irony of the death of 35mm, Shackleton jokes, is that the switch to digital has resulted in the “commensurate rise in the standard of projection” — those venues still able to project celluloid really know what they’re doing.

The Afterlight is transforming, though. And it’s not just the expected wear and tear of projection, including the flurry of scratches that appear every twenty minutes or so, on either side of the reel changes. Out of practical necessity, The Afterlight was printed on colour film stock, meaning that any deeper scratches eat into the top layer of emulsion, revealing glimpses of green dye beneath the monochromatic skin. Gradually, Shackleton tells me, his black and white film is turning to colour. And there have been changes to the soundtrack, too — an abrupt and menacing bump can be heard just before the end credits.

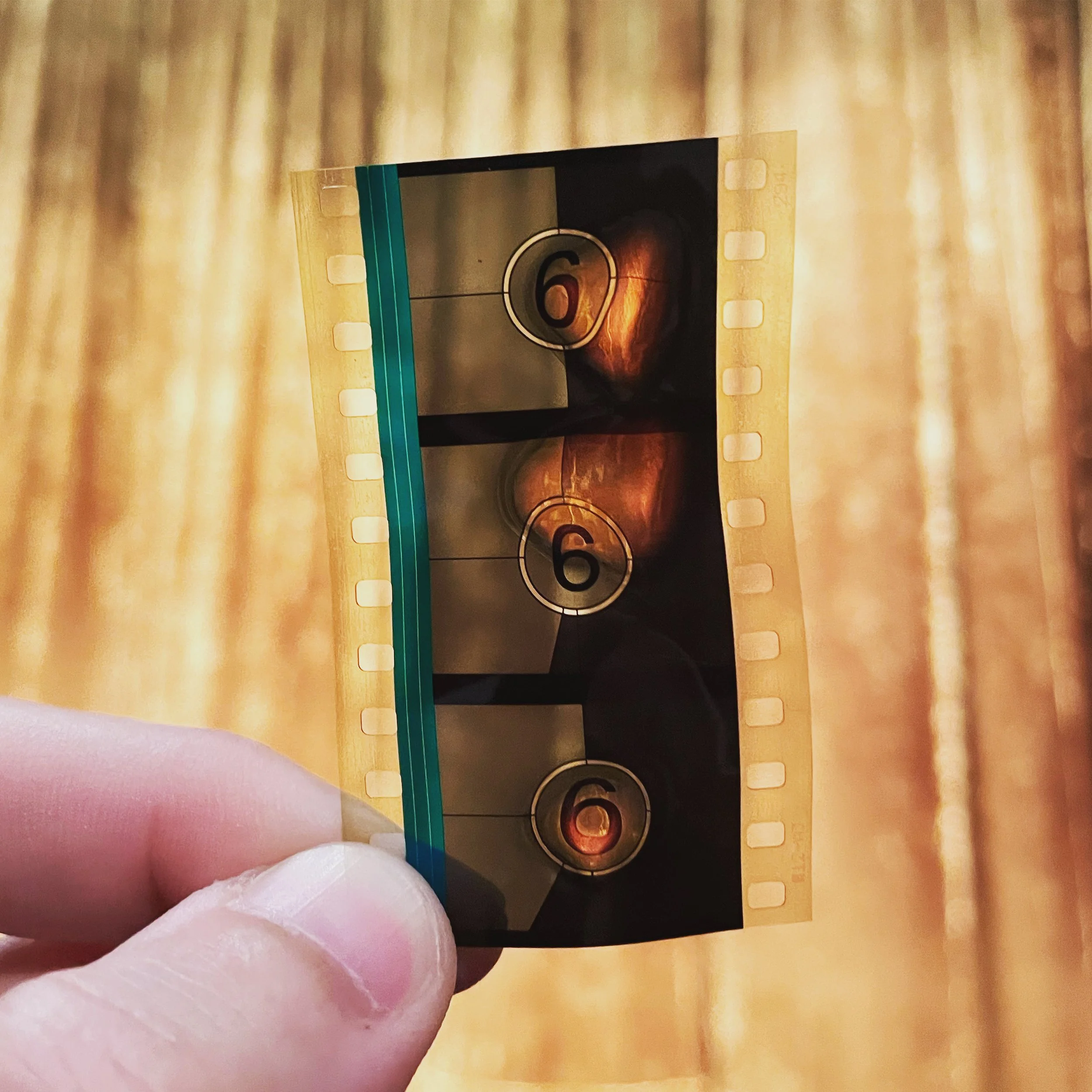

One change in particular, however, crosses over from the conceptually interesting into the uncanny. About twenty screenings in, Shackleton was handed three frames from the film which had been clipped out by another projectionist. These frames, part of the beginning of the film’s countdown sequence, had been burned through, leaving them scarred with ominous orange-red burns. Only later did Shackleton realise, as if a joke on the part of an already especially eerie film, that the frames which had been excised bore the numbers 6-6-6. A haunted medium indeed.

[1] Andre Habib, “Ruin, Archive and the Time of Cinema: Peter Delpeut’s Lyrical Nitrate,” SubStance, 35:2, (Johns Hopkins University Press: 2006) https://doi.org/10.1353/sub.2006.0034, 122. Emphasis added.

[2] Terry Mikesell, “Group’s Rescue of Old Films Preserves Glimpse Into Past,” The Film Foundation, (23 Feb 2017), https://www.film-foundation.org/columbus-dispatch.

[3] Charlie Shackleton, “I made a film that’s designed to be lost — and that’s not so different from Netflix,” in The Guardian (7 Oct 2021), https://www.theguardian.com/film/2021/oct/07/film-lost-netflix-the-afterlight-london-film-fesitval-digital-media.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Habib, “Ruin, Archive and the Time of Cinema,” 121.

[6] Paolo Cherchi Usai, The Death of Cinema: History, Cultural Memory and the Digital Dark Age (Wiltshire, The British Film Institute Press), 120.

[7] Cherchi Usai, The Death of Cinema, 105.

The inaugural Film on Film Festival takes place at the British Film Institute from 8-11 June 2023. Charlie Shackleton’s The Afterlight screens on 10 June.

Theo Rollason is a film writer and archivist based in London. They are particularly interested in experimental cinema, artists’ moving image, and the politics of blockbusters. More of their work can be found at theorollason.cargo.site.